Future Youth Project's Trip to Ukraine 2010

The purpose of the journey was firstly to meet the people at Happy Child (a Ukrainian charity) who are working tirelessly to change the system of institutionalisation that seeks to envelop all those with special needs in Ukraine and secondly to visit Kalinovka an institute currently housing 160 of these 'unwanted' people.

Journal of Visit 29th July 2010

After a 4-hour flight we landed in Kiev and walked out onto a baking hot runway. The 40 degree heat hit like a wave of instant lethargy but luckily for us an angel in the form of Happy Child volunteer Anna, scooped us up. Anna is an incredibly hospitable and entertaining local lady whose infectious energy and sharp wit saw off our fatigue for the next few hours. She showed us some of Kiev then fed and watered us before seeing us onto the overnight train to Zaparozhye for the second leg of our journey.

I imagined an endless train ride to be the ideal tonic for our tiredness; we could just sit and watch the geography of Ukraine unfold before our eyes. The real world tends to shatter such romantic thoughts however and true to form reality hit by supplying us with a train whose air conditioning had broken down....and whose windows did not open.

Sitting in a baking hot sealed metal tube with rivers of sweat running down us, we were not feeling particularly sociable but no sooner had Anna waved us goodbye than our next set of charming Ukrainian acquaintances popped up. They were a couple of medical students from Zaporozhye who were to share our compartment and who helped us laugh off our predicament with the joviality, energy and friendliness so typical of Ukrainians. They offered us some bottles of warm beer and then out of 4 layers of plastic bags they produced a whole dried salted fish to share with us. Zena and I got into the rhythm of chewing a small piece of fish followed by a swig of beer whilst Simon politely declined looking uncomfortable enough with his proximity to the odourful carcass. The rest of the occupants of our carriage dealt with the smell stoically, it was after all one of their fellow countrymen who had invited us to sample this local delicacy.

The night's sleep was sporadic. I love to sleep on trains but this time heat prevented any kind of deep sleep and I woke often. The train stopped twice and whilst others slept all around me, I gazed out at the vast, empty stations, only dimly lit by the odd orange street light in the otherwise deep black landscape. Enormous old diesel engines emerged from the darkness pulling endless lines of goods trucks full of coal and wood and at one station another passenger train going in the other direction pulled up a few tracks away. It was quiet, full of other sleepers but as we pulled off I caught the eye of another insomniac traveller looking out into the night on her own journey across this vast ex-Russian state.

The train journey took 12 hours. The first part of which we travelled through thick black forests whose giant trees made the train feel like a tiny toy. There were wolves, wild boar and bear in the woods according to our two Ukrainian cabin mates. After hours of forest the train clackety clacked out onto flat grassy plains and we were finally traversing the Ukrainian steppes, the unforgiving, barely inhabited, rocky grasslands in which Kalinovka 'Internat' was built.

30th July 2010

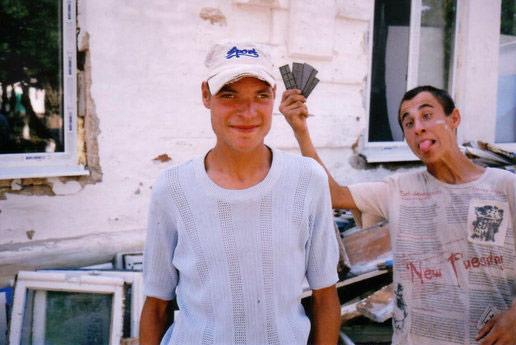

At 7am we lugged our camera equipment and other bags off the train, once again to be met by a local host. This time we found ourselves in the capable hands of Happy Child founder, Albert Pavlov. He greeted us and confirmed we had arrived in the middle of a heat wave and that in Moscow (due north) they were experiencing the highest temperatures since records began! Zaporozhye was, he said, hotter than Kiev and the sun, barely up yet already scorching hot, confirmed this. My head, fuzzy from the heat, did not feel sharp enough to talk let alone photograph. Once again my western weakness was apparent, the Ukrainians are tough creatures not likely to let a little heat wave slow them down.

Soon we climbed on board one of the many mini-buses that constantly zipped in and out of the station. They were mostly Mercedes vans kitted out with as many seats as could be fitted in them and then packed to the brim with people sitting, standing or struggling down the aisle trying to get out of the one door. Inside it was like an oven!

The bumpy half hour ride out of town passes quickly as we relax in the constant stream of enthusiastic talk from Albert. I have many questions about both Happy Child and Kalinovka and he has all the answers. Just as the town starts to give way to greenery we turn into a rambling housing estate dotted with crumbling tower blocks, in one of which is Albert's flat. He shares his 1 ? bedroom flat with his pregnant wife, their daughter and three adoptive teenage sons. Albert is only 30 himself, yet has dedicated his life to helping many young people stuck in state orphanages and institutions. We were welcomed into his home like old friends.

31st July 2010

After a night in the teenager’s bunk beds and a breakfast of eggs, tomatoes and bread, we meet Vladin who is to take us to Kalinovka in his (locally manufactured) car. Two and a half bone-shaking, blood-curdling hours later we arrived at the 100yr old Mennonite farmstead which had, at some point in the last century, been converted into a home for the 'unwanted' people that make up the 160 residents.

Kalinovka is both a working farm and an institution for disabled people. There is one vast main building surrounded by beautifully kept flower beds and trees, an apparent oasis in the otherwise empty, dry landscape. This building holds the directors offices and is also home to the only mixed group of young girls and boys. Scattered around this main building are various other solidly constructed but crumbling buildings holding the children with severe disabilities, another group of more able-bodied children and further away, near the dining hall, the adult male population of Kalinovka. The buildings are connected by roads and walkways some with old avenues of trees shading them, others decorated with colourful metal signs holding paintings of children’s cartoons. I have the strange sensation I have stepped into the grounds of a boarding school from the set of a Midwestern American musical.

We meet the extremely pleasant director of Kalinovka during a formal welcome in his office. It is also the first time we meet Julia, an 18 year old student from Odessa who translates for us. The director has to leave Kalinovka for a couple of days but agrees to let us have free reign to film and photograph as we wish with Julia as our guide. In order to gain this precious carte blanche I have repeatedly reassured him, over the last few months and today, that we come to Kalinovka as friends wanting to help with positive change not to create a media scandal like those before us. Compared to the paranoid directors I have met at other institutions I could see straight away we would be able to work with this kind man. Unfortunately his agricultural background leaves him unqualified to take an institution for the disabled into the 21st Century but that’s where FYP and Happy Child come in....

Julia shows us to our apartment; it is comfortable but has no running water. The kitchen consists of a fridge and a table; the bathroom, a mirror and bucket of water. The water is drawn by hand from a well which is filled by tanker every few days. We decide not to risk drinking it under any circumstances.

By now we cannot wait any longer to meet some of the kids, the ultimate purpose of our long journey.

In Building One we meet the only mixed group of young boys and girls. The room they occupy is jolly and well supplied with toys but I am struck immediately by the volume of the cartoons been played on the television in the middle of the room. Opposite this old fashioned TV set sits one of the ladies that look after these children in a ratio of about one to 12. Over the next two days I get used to the constant din of that television (and others) and the carer sitting opposite watching it as the children bounce off their never changing four walls.

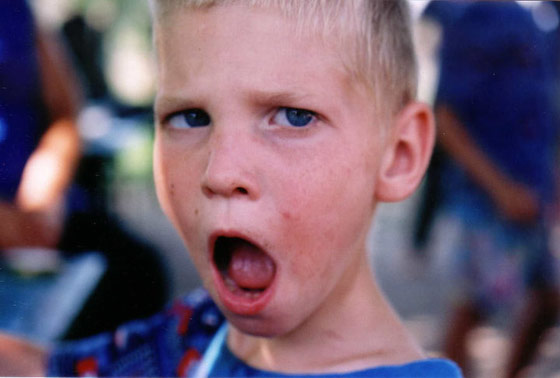

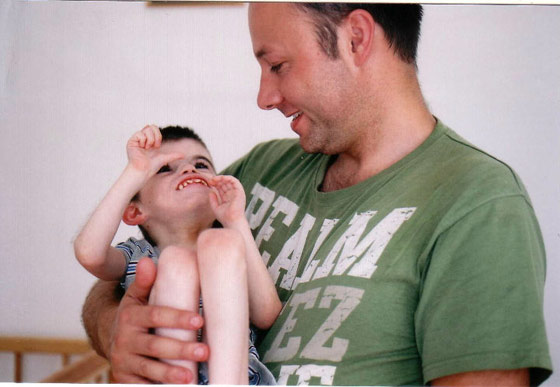

As Zena, Simon, Albert and I walk into the room we are each instantly surrounded by children clamouring for attention. Hands reach, shrieks of joy ring out and smiles are abundant.

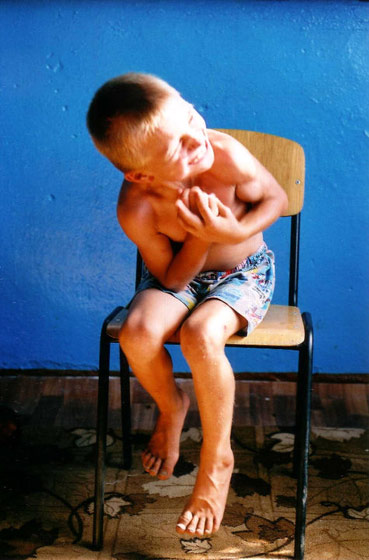

Our attention is at first grasped by the most able bodied children who get hold of us quickest whilst others in wheelchairs or shuffling along the floor on damaged limbs try to get to us next, all desperate for attention. Whilst I greet a girl and a boy in wheelchairs in front of me, a 5 year old with Downs Syndrome tries to grab me from behind. I turn and give her my hands and she pulls with incredible strength causing me to fall off my chair. A shout from the carer and she stops, only to try the trick again a second later, I am ready for her this time.

She is serious (some of the children don't smile) and every time I turn away from her she pushes or pulls me. When I give others attention she grabs at my dress and I hear the seams rip, I laugh it off, it feels like the only appropriate reaction. Having got my attention again she lets go of her grip a bit and I start to play with her hands but a sudden sharp pain causes me to spin back round to the wheelchair bound children. One has just scratched my neck and it’s starting to bleed. I stand up for a second to regain some composure.

Simon and Zena are having similar experiences, Zena's camera bag is being riffled through as she tries to remain calm and engage with as many youngsters as she can. Simon looks like a human version of a wooden mug tree with tiny children hanging off him all round. It is seriously intense but everything that is happening to us is happening because these children live a life of under stimulation, in which they are constantly underestimated and ultimately unwanted. I feel as responsible for this as anyone, perhaps because I am a parent and these are parentless children.

Despite the intensity of the experience it is a joyful and at times hilarious one. When Julia suggests we continue our tour I find it hard to move on, knowing each one of these children needs so much more than what he or she is getting. I have to remind myself I cannot solve all their problems myself and try to stay focused on the bigger picture.

Lunch might seem like a welcome break from the growing intensity of Kalinovka but to get to the dining area we have to walk through the open space that holds the adult male residents. The more trusted of them roam free and approach us with smiles and cautious hand shakes whilst the others are kept in what can only be described as a cage. The metal bars on the 4m x 8m box only half hide from view the horrors of the lives of the most disturbed of the adult men. Having only one carer per 10 or so men it is plain to see why they have to be kept in one place but this cannot justify the degradation, darkness and despair emanating from that cage. Some of the young men are naked, some howl, some can be seen self-harming. These men need one on one attention and special care, something Kalinovka is struggling to provide.

We avoid looking at the cage. With one exchanged glance Albert sees and agrees with my horror.

We walk through the motley crew of swaying, smiling, rocking mumbling characters that wander around trusted to have more freedom and head for the steps of the impressive building that holds the kitchen and dining room. I am only vaguely aware of a disturbance behind me when suddenly a young man runs straight at me and before I have a chance to react he has planted his nose on my chest taken a deep breath and run off! Once again I manage to quickly turn my alarm into humour and the extraordinary moment passes as just another Kalinovka novelty. I am told he likes the smell of women, a tragic reminder of the fact these men have been starved of female love all their lives, first by the lack of a mother and now the lack of any kind of social life outside their all male group.

As we climb the steps of the dinning building I look back at the men dotted about in the long grass and dappled shade afforded by the poplar trees blowing in the merciful breeze. Some men are watching us fascinated by the visitors, whilst others remain in their own worlds picking at the grass and rocking or moaning and as I look back at the scene I feel as if I have landed on the film set of some strange hybrid production of Little House on the Prairie meets One Flew Over the Cuckoos nest.

Lunch is far more delicious than we expected and we are told the residents get the same menu of fresh tomato salad, deep red borscht soup and fried river fish. I can almost believe it considering all the ingredients are locally sourced, something which in this part of the world makes them cheaper. I start to wonder what is on the menu in the months Kalinovka is cut off by deep layers of snow. The local delicacy is fat, served in slices.

After lunch we decide to forgo the suggested rest, all of us convinced that full bellys and 40 degree heat will result in passing out and not being able to get up again, so we say we want to keep going and head off to meet the older children playing in an outdoor space. This group are all boys; those with crippling cases of Cerebral Palsy are confined to raggedy wheelchairs or rock on the floor whilst others with less restricting disabilities such as Downs Syndrome run around freer but plainly bored.

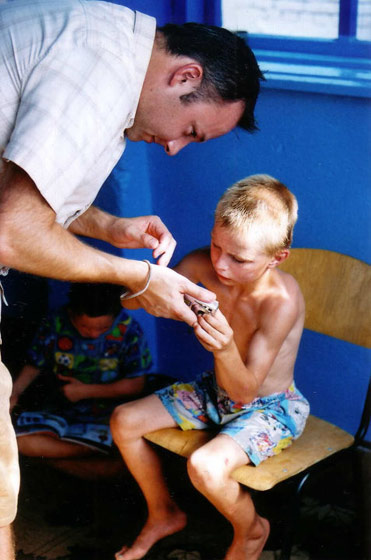

As I approach this group I spot an older boy with thin twisted limbs looking at us from the sidelong view his spasming turned head provides. As I look into his eyes I become aware of the first inkling that this boy will change the course of my life. His name is Alyosha and until Happy Child realised he was a sensitive intelligent human being, he had been left in a room of severely retarded children, bed bound and staring at the same white walls for years on end. The carer with him tells us he once could walk but since being in Kalinovka and bed-bound his joints seized up. Alyosha beams at us showing no bitterness or anger at his fate and, in that moment, I learn how to be a better person.

Alyosha is the star of this particular group because since Katya (one of the carers provided by Happy Child) has started teaching the kids to thread glass beads Alyosha has proved to be incredibly adept. It seems miraculous that amidst the chaos of the hyperactive overexcited children that bustle around him and his own battle with the spasms that wrack his body, he is able to suddenly find a moment of inner calm when his body and mind work as one and he leans forward and threads a single tiny bead onto the end of the wire he holds in his twisted hand. He then turns the wire back over the bead and back through the hole to knot it. Katya says that the more able bodied children can thread the beads but only Alyosha has learnt to form them into the leaves and petals that she can join together to form the beautiful bead trees.

I keep an eye on Alyosha over the next few days and I often see him left in the sun in the 40 degree heat, sometimes propped up against the boiling metal bars of Building Three's outside pen, without even a hat to shade him. I try to imagine the same boy in the UK, he would certainly have his own wheelchair and not have to share rendering him immobile for the majority of the day; he would have physiotherapy everyday to loosen his seized muscles and medication to relieve his constantly spasming limbs; he would have friends, and a social life; he would have a computer to write his thoughts and communicate through; he would be able to see the world beyond the gates of Kalinovka. His brain and body would be nourished and his generosity of spirit would be rewarded, as it should be. I feel suddenly helpless and pathetic and cannot keep back tears. Zena and Simon take me away and tell me they feel the same but that “at least we are trying to do something”.

Zena spends the afternoon filming the kids whist I photograph and Simon does his best to fend of the endlessly curious children, pulling their hands off Zena's tripod, or out of his pockets or off my camera lens– it is a full time job! Mercifully around 5pm the day starts to cool and we contemplate something we have been desperate to do since we heard of Kalinovka – take some of the children for a walk.

After 10 minutes of choosing which children to take, a harrowing experience for those both choosing and unchosen, we set off on our walk. 'Walk' is a poor description of the fine array of styles of forward movement these children come up with to keep up with us. Out of the three wheelchairs none have footrests and only two have handle bars, one has no back and all have flat tyres but this is no obstacle for the kids of Kalinovka who not only get the wheelchairs moving but have fun messing about with them to the great joy of the primary riders.

Mourad an older quite heavy boy hangs off Simon's and my arms and walks along the hot tarmac road on bare twisted feet. As his progress slows due to the pain in his unused limbs, the smile on his face never wanes. Amongst the more able bodied children there is running, shrieking, flower picking, pointing shouting and general joy. Although not all the children are joyous, a couple are very serious and one particularly looks scared and scuttles in front then runs back only to decide he can muster up the courage to join us again. I imagine he is experiencing pleasure from the walk but is unable to express it or perhaps even understand it. I am reminded of the terrible abuse some of these children have suffered locking some (like this child) in a world of their own, full of fear and stress.

As the sun sets we reach the outer perimeter of the institute and there is a sudden excited buzz amongst the children – they have never been beyond this point. We walk a little further so we have taken them outside the institute, so they have been 'somewhere else'. This feels important to me, as if we can free them if only for a moment.

The time comes when we have to tell the children we must return them. The children are disappointed but stoical. All except one that keeps on pointing over the horizon (something a lot of the residents of Kalinovka do) and shouting something repeatedly to Albert, who tells us he is shouting that we should go to the sea. Albert and I agree we will try to find the lake we have discovered on dusty local map he found in the apartment..

The next morning we pile into Vladin's car on a mission to find the lake. We drive out of Kalinovka's rusty gates and take a dirt track over a nearby hill and there, like a mirage in the hot dry landscape is a beautiful blue lake. Albert cannot believe his eyes, for three years he has been driving children to the Azov sea a few hundred kilometres having no idea the lake was there. The moment becomes surreal and I feel again the dream-like quality of reality at Kalinovka.

Albert and I chat about the possibilities of this place; we can build a platform into the lake and take children here for swims, we can make Albert's famous camping trips within yards of the home so more children can get involved and get out of Kalinovka for a day or two.

Then re-engaging with the moment we decide to pick up Seryozha and Alyosha and bring them for a swim.

Albert is incredibly brave with the people he deals with and faced with obstacles most of us would find impossible to negotiate he leaps straight in. He hauls the wheelchair bound kids into the car and tells me not to worry that we cannot take their wheelchairs with us.

Soon Zena, Simon, Albert, Vladin and I are sitting by the lake with Seryozha and Alyosha sitting as best they can on a blanket beside us. We all look out across the calming cooling blue water of the lake and watch the peaceful scene of a fisherman bringing in his nets. Seryozha is playing throwing stones and laughing – he seems as intelligent as any boy his age. Alyosha is sitting up with my help and also trying his hand at throwing stones. Its a beautiful moment and instead of the institutionalised and the free, we are just people, enjoying the day.

Albert and Vladin check the banks of the lake for somewhere to take the children into the water. It does not look good, they are slipping in deep mud from which vertical reeds stick out like sharp arrows. I wait for them to say its impossible but instead Albert returns and asks Alyosha if he wants to swim. Alyosha excitedly agrees and Albert hauls him down to the lake, I have no idea how he finds the strength but with a little help from Vladin and I, Albert gets Alyosha in the water and encourages him to swim. It’s a success and Seryozha has his turn next. I swim too and I will never forget the look of nervous excitement and joy on the faces of the boys as they are held in the cool lake and their limbs are free to float and move gently in the supporting water. They are buzzing and seem more alive than ever.

After the swim the boys have a few more minutes to relax before we head back. I sit in the car and watch them, Seryozha is joking about with Vladin and Albert whilst Alyosha stares out across the lake his body suddenly free of its usual spasms.

The stories of the characters we have met at Kalinovka are endless tales of tragedy obscured by the positivity and love pouring out of them. It strikes me that out of all the orphanages and institutes I have been to over the years, Kalinovka fills me full of the most hope. This place is in a desperate state but given the right support it could be a beautiful place with all the facilities needed by these children and adults to build a life for themselves.

As I wrote this report I felt an obligation to those at Kalinovka who had made our stay there such a wonderful experience. The story I tell is a positive tale but one must not forget the underlying and shocking reality faced by those trying to look after these children and adults. Here are a few hard facts; in Kalinovka there is no running water. This is a massive problem when caring for large numbers of sometimes incontinent and often ill people. Toilet arrangements are horrendous. Basic hygiene such as washing hands is almost non-existent and there is little water and no soap. To drink the children share a single cup, which they use to scoop water from a communal bucket. Some children play with the water in this bucket with dirty hands. Most of the children have no medicines to help with their syndromes, no anti-spasmodic drugs for those wracked with spasms, no drips for those dying. The wheelchairs they use often injure them by tipping them out, dragging their feet, giving them sores. They have no future beyond the walls of Kalinovka unless they are lucky enough to meet someone who is brave enough to look after them in the outside world.

The graveyard at Kalinovka - the last resting place for 400 children